During my career, I’ve spent time at every point along the investor food chain. I’ve experienced the purity of being a venture-backed entrepreneur in the dot-com bubble. Then I founded one of the first seed funds in New York City. Now I’ve gone back to the operating side.

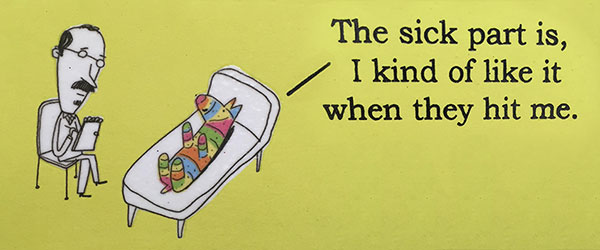

I was on a panel recently and somebody asked me what that transition was like — from entrepreneur to fund founder and back to entrepreneur. My answer: “That’s easy. I went from being the piñata to whacking the piñata and then back to being the piñata.”

Like any good joke, that answer contains more than a grain of truth. There’s an inherent tension in the startup/investor dynamic. The entrepreneur seeks venture funding. The VC firm provides that funding in order to achieve outsized returns in a relatively short period of time. And the VC firm, in turn, has to answer to its institutional investors who have the same goals, and the institutional investor has to answer to its constituents. That’s a pretty long line of people eager to take a swing at the piñata. And the more bats you hand out, the more candy you have to provide.

The uncertainty of when the candy will rain down can cause problems. “Eventually” and “soon” are staples of the entrepreneur’s glossary. That’s particularly true with early-stage tech where all assets are illiquid. Even if your investment grows, you don’t have much to show for it until the company sells, goes public or allows insiders to sell some in a round of funding. You’ve just got paper wealth — which has about as much practical value as an unbroken papier mâché piñata.

That can breed impatience. Early on there are minor exit opportunities, and smaller investors would be more than happy to sell quickly with a big return. It might not be at the right time or the right market, but they often don’t care. Small funds need to show their investors they are producing liquid returns. They’re under pressure — personally to their partnership or to the fund’s investors. So a lot of them get angry: “Why isn’t the piñata breaking? Whack it harder!”

As a guy who goes to a lot of kids’ parties these days, I can assure you that a piñata breaks when it wants to break. And it’s almost never on the first whack. I understand the anticipation. Everybody wants the candy to come bursting out, and when somebody gets a good whack at the piñata and it doesn’t break everybody’s reaction is “Awwww!” That’s like a company that almost gets bought but then no deal happens.

Bigger funds require bigger exits, which takes longer. You’ve got investors with different motivations and different levels of pressure that they want to put on a deal. It’s like angels and seed funds are given plastic bats to swing at the piñata; larger funds get lead pipes. And a lot of times the fateful whack isn’t the one you expect. It has to be the right person swinging the right-sized club at the right moment after the right amount of softening up and with the piñata at just the right angle.

The entrepreneur and employees want their candy. Investors want their candy. It’s a system of relatively aligned motivations.

And you know what? I wouldn’t want it any other way.

Chairman and Founder at PebblePost, former VC in adtech, long-time endurance athlete, happy dad to “The Heathens.”

Chairman and Founder at PebblePost, former VC in adtech, long-time endurance athlete, happy dad to “The Heathens.”